02 JanThe Science of Reading Science

At School for the Dogs, we pride ourselves on training dogs using positive reinforcement-based, force-free and humane teaching methods. Many of us are certified through the Certification Council for Professional Dog Trainers, which conducts exams that ensure those who are certified can “demonstrate a mastery of human, science-based dog training practices.” While that all sounds very professional and scientific (for lack of a better word), it can be hard to parse what it really means to a dog owner choosing a trainer. As we have noted in a previous blog post, the certification process for dog training can be tricky to comprehend. We think it's great when trainers are up on scientific studies; too often, however the studies that are cited aren't as worthy as they may seem.

In this initial series of posts, I will be presenting recent discoveries in dog behavior, cognition and sciences to help you navigate the wordy, verbiage-driven world that is science.

For this inaugural post, I will discuss what to look for when reading research and discuss a recent study regarding resource guarding.

First up….

HOW TO DETERMINE A STUDY'S WORTH

As clearly laid out in this post, there are a number of benchmarks to keep in mind when reading a research article. I have laid out some of my major ones below.

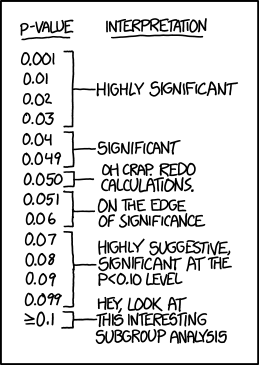

1) Statistical Significance:

The P-value in scientific hypothesis testing is one of the more niggling, annoying items in science. Most scientific research utilizes a p-value of less than (<).05 which itself is an arbitrary value. If a study determines statistical significance in a comparison at <.05, the researchers are fairly confident that the difference is not due to chance and they can reject that the two populations they were comparing are the same.

2) Sample Size:

Most researchers agree that a sample size larger than 30 data points (eg: individuals, trials etc) can provide some solid results. Essentially more items pulled from a population can provide more potential truth of what they are testing in the population.

3) Confounding Variables and Assessing Limitations:

A hallmark of good science for me is being aware of the potential issues of a study. Research does not exist in a bubble and especially in behavioral research, there are many external and internal items that can affect a subject. Science can also never be perfect so being aware of what could or couldn’t be done in the study can allow future researchers to get “closer to the truth.”

4) Where the Research was published:

“Peer-review” is a buzzy term in science but that essentially means that other researchers in the field reviewed the article and determined its methods and research were sound. There is a lot of drama that is involved in the peer-review process — another topic for another day — but generally it is considered a good standard for publishing research. In this day and age of science, self-publishing online is an option but that clearly bypasses the peer-review process and “un-sound” science may be published.

WHERE TO FIND “GOOD” SCIENCE

Tracking down good research can be just as difficult as reading such research. Much of the “science” the common person gets nowadays is filtered through the media. Many news programs, cherry-pick the more sensationalist aspects of a research study leading the public to ignore the framework in which the research was presented and what the scientists actually meant. John Oliver did a great bit on the media re-portrayal of science. My recommendation if you are really interested in a topic is to go to the original source and read it for yourself. You will usually find that the scientists made much less majestic, earth-shattering summations than the media

To get a little bit more perspective on the twist the media can put on things, here are a couple dog-related studies that have been blow out of proportion in the media

- Science showed that dogs don't like being hugged.

- What the media failed to note was that the data obtained by “causal observations” (as quoted by the scientist who led the study; the study was not published in a peer-reviewed journal)

- Puppies love our baby talk.

- The research found that puppies were reactive to dog-directed (baby-talk) speech especially with the variance of pitch but there was no difference in reaction in adult dogs; apparently we our chatting to dogs of all ages might just be more of a result of use trying to facilitate interactions with our non-verbal furry friends

- We were even part of the media uproar surrounding this study.

THE STUDY

Scientists at the University of Guelph recently published data on the first study to examine factors associated with the presentation of non-aggressive and aggressive forms of canine resource guarding. As defined by the researchers, resource guarding is one of the most common types of aggression and that it is “used to achieve or maintain access to an item of perceived value.”

They presented three forms of resource guarding:

- Rapid ingestion- the rapid consumption of an edible item

- Avoidance- blocking access to an item through body position or location

- Aggression- growling, baring teeth, snapping or biting.

The study was conducted using an online tutorial, assessment quiz and a questionnaire recruiting over 3000 participants, in the end, accounting for a total of 4857 dogs. A number of different variables in relation to resource guarding were assessed. Among them were a dog’s impulsivity, fear, training history, the owner's attitude and the household make-up.

A summary of the findings are below, with some non-scientific translations provided

- Dogs who can reliably leave or drop items on command were .46 times less likely to display biting aggression compared to just threatening aggression.

- The more reliable a dog was on responding to a “leave it” or “drop it” cue, the less likely they were to potentially bite if a resource was being taken away.

- Manipulations to a dog’s food during early development appear to have lasting effects on future behavioral responses.

- Messing around with your dog's food whether taking it away, adding things to it or general handling of it had an impact, either positive or negative, in the future.

- Dogs who had a food bowl removed while eating following one year of age were 1.88 times more likely to demonstrate an increased frequency or shift towards a more undesirable type of resource guarding

- Removing a dog's food bowl is a really common way people think they had reduce their dog's tendency to guard or think no one else can touch their food. What this study was able to show was that it actually might be doing more harm than good. Think about it from a dog's perspective- your approach begins to mean their food is being taken away and who knows if they are getting it back.

- Dogs who had highly palatable foods added to the food bowl while they were eating were more likely to demonstrate a decreased frequency or shift to a more desirable form of resource guarding.

- The simple addition of high-value treats to your dog's food bowl can start to get them excited about your approach. Your approach now means bacon bits might be getting added to their kibble which is amazing! They will want you to come to their bowl more often!

The researchers noted that the participants for the study were self-selected, so while the sample was large, it might not be representative of the entire pet dog population. The survey also required the owners to think back on past events so some events might not have been remembered entirely correctly. While this study was the first of its kind and presented a good starting point for understanding what may contribute to resource guarding, it was limiting in itself understanding of causation of resource guarding. Future studies could provide a analysis from puppyhood to adulthood and how different techniques may affect resource guarding.

SO WHY SHOULD YOU CARE?

A huge takeaway from this study is the concept that how we interact with our dogs over their resources can have a major impact on their resulting behavior. Dogs do not understand that their prized resources (whether food or toys) will be returned to them- they just know what is going on at the moment and they would like to keep their stuff.

From a scientific viewpoint, this study is able to provide some solid data drawn from a large sample. This does not mean it is the end-all-be-all for resource guarding research but lays a solid groundwork for how to move forward in our understanding.

And from a training viewpoint, the groundwork provided by this study, can help trainers and owners move forward with a better idea of how to tackle such a common issue and help provide dogs and their owners with some level relief and behavioral change.