24 JulEpisode 69 | “Mean Talk,” Mouse Traps & Water Guns: The Lassie Method

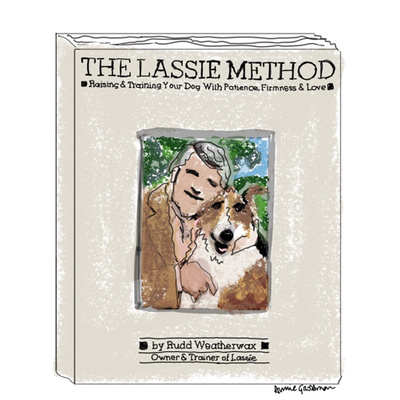

A few weeks ago, Annie interviewed Jon Provost, who played the little boy Timmy on the Lassie TV series in the 1950s and 60s. He talked a little bit about Rudd Weatherwax, who was Lassie's owner and trainer. Jon talked about how Weatherwax only trained with praise and rewards, and Annie described him as "progressive." After the episode aired, however, she found some old videos that showed training methods that suggested otherwise. In this episode, Annie reads from Weatherwax's 1971 book, The Lassie Method: Raising & Training Your Dog With Patience, Firmness & Love, and considers the pros and cons of his suggested training techniques.

Subscribe: iTunes

Transcript:

Annie:

So a few weeks ago, I interviewed Jon Provost, the actor who played Timmy on the TV show Lassie when he was a kid. And we talked just a little bit in the episode about Lassie's trainer and owner, whose name was Rudd Weatherwax. And he was kind of a big deal in the world of commercial dog training in the early to mid 1900s. He trained Asta for The Thin Man. He trained Toto for The Wizard of Oz, but Rudd Weatherwax wasn't really the focus of the interview.

And, you know, I admit in some episodes I have more of an agenda than in other episodes. Some episodes of this podcast, I am just interviewing people who have done interesting things with dogs or are working with dogs. I like stories about people and dogs, and I like sharing those stories, but of course I am a dog trainer. I am opinionated. I have very specific points of view on the subject matter.

But Jon Provost in our conversation together, he and I didn't get very technical about exactly how Lassie was trained. But Jon did talk about how Rudd used methods that were entirely based on praise and rewards. And I just took Jon's word for this. And I talked about what a progressive trainer Rudd Weatherwax was, and how he clearly had a keen understanding of how to use positive reinforcement, which I am sure is true because I don't think you could get a dog to do many of the things Lassie does on that TV show without being very good at using positive reinforcement to encourage behaviors and get a dog to do it in a way where the dog is looking so, so happy and healthy.

But two things. One, I think I just assumed that someone who spent so much time on set with a dog and their trainer would be able to recognize what they were doing as far as training goes. Like I think I just take for granted at this point that someone could break down what someone's training methods are or what their approach is. But in reality, I know things can seem kind of opaque when you're watching training happening. And if you don't know what to look for or what you might not want to be seeing. I mean, I don't know. Also I'm talking to a man who is recollecting things that happened 60 years ago when he was a kid.

The other thing of course, being that Rudd Weatherwax maybe really was all praise and reward with Lassie on set or whenever Lassie was with Jon Provost. They worked together very closely for many, many years, the dog who played Lassie and Rudd Weatherwax. Interestingly, they only ever had one Lassie at a time. I learned that speaking with Jon. Anyway, that dog, whichever Lassie it was at the time, and Rudd Weatherwax I'm guessing had a very strong bond. And I'm sure that that dog was tuned into understanding what Rudd Weatherwax wanted with very, very little force or coercion necessary because they had such a history working together.

And also, because again this is me guessing, that they did a lot of training for him to learn new things off set. So by the time they got onset, it was more about maintaining those behaviors, which could be done using positive reinforcement. Cause that's the way that you're going to encourage behaviors that you want to keep happening. And if you're doing something on a set in front of a camera where they might do several takes, you want behaviors that are going to keep happening.

And probably also Lassie was really good at learning from Rudd Weatherwax, because no matter what methods he was being taught with, he was learning all the time probably new things, or having to do new things on set and probably was just a really good learner. So if he was using negative reinforcement or positive punishment, those methods that we really are always trying to avoid, it was probably pretty subtle. And the dog probably learned very quickly. So I don't think it's really unimaginable that his specific methods really were weighted towards praise and rewards and treats and affection and attention, et cetera, et cetera, when he and the dog were on set.

But right after the episode aired, Libby who helps me out with the show sometimes, sent me these videos of Rudd Weatherwax, kind of like rare archival footage kind of stuff — we take for granted now that you can see videos of anyone doing anything — but these old videos from maybe the ‘60s, ‘70s. And his methods did not look like they were based in praise and reward. So this left me feeling kind of guilty that I was so quick to describe what this long ago trainers' methods were without really researching it.

So I got his book, which is called The Lassie Method: Raising and Training your Dog with Patience, Firmness and Love. It's a full color book, about a hundred pages published in 1971. And on the cover, there's a picture of him and I guess Lassie. And this guy is just awesome looking. He is wearing a brown suede jacket. He has silver hair and huge dark eyebrows. He kind of looks like — actually, he kind of looks like Johnny Cash. And he's wearing a silk scarf, or what one might call a silk foulard, and a gold pinky ring.

He talks about how he grew up with collies in New Mexico. His father herded angora sheep, but eventually the family moved to Los Angeles, and he got a puppy named Wiggles, a terrier. And when he was a teenager, he would just train the dog to do tricks for fun, and the dog and he used to hang out outside the movie studios in LA, hoping to get picked off the street as extras, which I guess used to be a thing. And eventually it actually happened and from that, being an extra with his dog, he ended up working for a man named Henry East, who was a big movie dog trainer at the time. And it looks like he also has a book that I now want to get my hands on, from 1933.

Anyway, I guess East was the one responsible for Asta in The Thin Man. And he started working when he was like 16. There’s a picture in the book of him in 1931 with Asta, the white terrier, and he's kind of holding treats over the dog's head, trying to get the dog to climb a ladder in 1931, it says. And there's this picture of him also in 1924, it says he's 16 years old, with this adorable puppy, and he's adorable. He has like this, a newsboy cap on and a white shirt with sleeves rolled up.

And he talks about, in these first pages, why it's so important to train a dog. He says:

“A fully trained dog is a happy dog, immensely more so than the untrained or sloppily trained animal. By being obedient, your pet earns additional praise and love, both of which he craves insatiably. He's not anxious, confused or upset by never having had limits set, or by not knowing what is expected or desired of him. A dog is an intelligent creature, and he doesn't enjoy being treated as a stupid sometimes amusing and sometimes pesty object. Certainly he's not rational in the matter of human beings, but he is capable of mastering a variety of difficult actions and is possessed of emotions which can be just as intense as your own. A job well done gives him a chance to show off. It builds his ego and strengthens his sense of worth, and it gratifies in a constructive way his need to apply his intelligence. And you'll appreciate him more, which means extra fondling and play for him and more time in your company. In short, if you love your pet, you owe it to him to train him.”

He also talks about what the advantages are to the person: “The advantages to you in having an obedient dog hardly need to be mentioned. Just think of living year after year with an unruly and willful animal, one convinced that the world exists solely to please him.” That's interesting to me, that it's “the unruly animal thinks that everything is existing to please him” and therefore why — why is the dog being unruly if things are around to please him?

Anyway, I'm continuing to read: “Contrast that with a dog who comes when he is called, who walks contentedly at your side. Okay, most owners will agree that training is a good deal for them. But a surprising number are reluctant to impose discipline upon their animals, are even tormented by the idea. ‘I just can't stand to oppress him,’ I've been told. ‘I don't want to break his spirit.’”

So much interesting stuff here to dissect. I mean, he talks about imposing discipline. I think of the training that I think of as good dog training, to be a training that does impose discipline. But I think I think of discipline as like boundaries. And discipline is also just like encouraging an animal to keep doing something because it's good, enjoyable, delightful, et cetera, and not because something bad is gonna happen.

But he's basically saying you want to have a trained animal because you might otherwise have an animal that's out of control. You might have an animal who is spoiled and thinks whatever he feels like doing is the right thing to do. Which, that's where I got stopped up for a second. I really had to think about that because my feeling is I want to train a dog who is really excited and interested in doing all the things I want him to do. So I don't think of that as spoiling.

And then he's pointing out how training is so good for a dog, and so it's silly for anyone to think that they don't want to train because they don't want to break the animal's spirit or oppress the animal. Oh, I didn't read that part. Actually, after that part, he writes “Nonsense to the idea that training would break an animal spirit or oppress a dog because a fully trained dog is a happy dog.”

I dunno. I mean, if somebody said to me, I don't want to do dog training because I don't want to break my animal’s spirit, I would say that the training is going to be good for the dog. But I think my reasons for why it's going to be a good, enjoyable thing for the dog and Rudd Weatherwax’s reasons are probably not the same.

Anyway, a few pages later, there's a photo now of him with the original Lassie, and now he looks — this is 1942. He looks more like — he's wearing like a kind of gangster Guys and Dolls-ish, like pinstriped suit. And he looks kind of like Ryan Reynolds, somewhere between like Ryan Reynolds and William H Macy. And he's talking here about how he was working with a dog who was like the backup Lassie on Lassie in the movie, because his dog Pal who had been handed over to him by a couple who wanted him trained and then basically like never picked him up. His dog Pal was well trained but not right for the part, because they wanted a female, and they also wanted a dog who had a white blaze up his muzzle, which his dog didn't have.

So Pal came on as a stand in for the film of Lassie, which came before the TV show. And there's this moment where they're shooting with the dog Pal. And he writes:

“A key scene in the script called for Lassie to swim abroad Swiftcurrented River. We took Pal about a hundred yards offshore on the San Joaquin River in Northern California, and I put him over the side and told him to swim in. He did!” You think he threw the dog over the side of the boat, and then told the dog to swim and the dog swam? [laughs] Okay.

“And then, on command, didn't even try to shake himself dry as a dog would normally do, but walked a few slow steps, let his head droop, then rolled over on his side as if collapsing with exhaustion. He held the position perfectly until the director Fred Wilcox yelled ‘Cut!’ And then when I told him, ‘Okay,’ he sprang up, shook himself, and bounded to me, and kissed me! Wilcox came over to us and his eyes quite literally had tears in them. In an emotional voice, he said, ‘Rudd, Pal went into the river, but Lassie came out.’”

[Whistled theme from Lassie plays]

Maybe I really am being a cynic here, and maybe he really did train Pal to do these things. But I mean, the dog's “head drooped, he rolled over on one side as if collapsing with exhaustion” — he just swam 300 feet abroad Swiftcurrented River! What'd you expect?

You know, there was this one time when I was working for the Animal Planet show Too Cute. I was an associate producer and I had to get baby ducklings for an episode, because there was an episode where the ducklings make friends with some mini Aussies. Super cute, as the title would suggest. And the producer was like, “You know, Annie, what would be really great is if you could get the ducklings to walk in a line and then, the puppies could watch them walking.”

So I had the ducklings in a box. I took them out of the box and they started walking in a line. Because that's what ducklings do. But I think people love to think that some people are magic magical with animals. And I got so much credit that day for getting those ducklings to walk in a line.

So I think Rudd Weatherwax was taking a little bit of credit here for a dog doing some doglike stuff. Sure, he says he did all of this on command, but that's kind of the secret about adding a cue or a command. Like I talked about in the episode a few weeks ago with the character in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, who knows there's going to be an eclipse. I mean, if you know there's going to be an eclipse and you point to the sky right before it happens, and you say “Eclipse!” It very well might look like the eclipse happened because you commanded it to!

Okay, fast forward a few more pages, and now we have a photo of him looking more like the Johnny Cash later version of himself. There is a Collie puppy, and he's kneeling in front of the puppy with his finger out, pointing at the puppy and the slipper in his hand, in one photo. And then in another photo, there is the same puppy with what looks like a string around his neck and Rudd Weatherwax is kneeling down and pulling the string up at kind of like a 45 degree-ish angle.

All right. So this is the section on puppies:

“Fix in your mind that the pup is not disobedient. This is a brand new world. He doesn't know what's forbidden and what's permitted. You have to show him consistency is vitally important. If something is a no, it's always a no. Don't let him get away with it just this once. That will utterly confuse him. You can't expect him to read your mind and know what days you're permissive and what days your usual authoritive self. Inconsistency demoralizes a dog since he can't possibly understand what is expected of him.

“Let's say our pup thinks your wife's new boots were designed, manufactured and purchased solely for his chewing pleasure. The first time he plops down, takes a boot in his mouth and begins to work it over, tell him in a crisp stern voice, ‘No! Bad dog!’ Dogs, even young pups are very sensitive to tones of voice. He may do anything from simply dropping the boot to retreating several feet and looking at you, anxiously. Praise him and tell him he's a very good and intelligent dog, and you're pleased that he responded so well. Pet him. Also, offer him a toy or something that he's permitted to chew on. This way, we give him a positive alternative. Most pups will require a few repeat performances before they catch on.”

Okay. This is Annie talking again, not Rudd. So yeah, dogs do respond to tone of voice. I agree with him there. But I wanted to point out that he says this way, we give him a positive alternative. That's like — ugh, the use of the word positive in this kind of way drives me nuts, because I feel like someone could point to this and say “He's a positive trainer, right? Cause he gave the dog a positive alternative?” Well, that’s not quite what's happening, but it is a good idea to give the dog something that he can chew on if he is chewing on something you don't want him to chew on.

Okay, I'm going to keep reading:

“When told no, some pups will simply glance your way, curious, with the boot still in mouth. With these, remove the boot repeating ‘No! No! Shame on you!” Then give the positive alternative. A few pups won't learn without stronger measures. They refuse to drop the boot, hang onto it when we try and take it, or grab it up again as soon as we drop it on the floor. Repeat “No, bad dog, no!” and snap your index finger, or the first two fingers against his sensitive nose. This will convince 99%.

“For the few that remain the command to stop can be coupled with a whack to the rump, with a few sheets of folded newspaper, which doesn't really hurt, but makes a loud intimidating noise. If he's fanatically determined, give him a slap, but be careful not to make it strong, on the underside of his muzzle. Be slow to take such a corrective measure. Give him the benefit of the doubt and assume he really doesn't understand until the moment there can be no more question.”

Okay, Annie, again now speaking. Wow. Okay. So basically ,like, hit the dog, but not too hard. If you don't do it too hard, it won't be that bad. That's like my summary of this paragraph. Continuing, he says:

“The defiant dog who understands perfectly well, but who rebels against your authority, is a different matter. Unless you're prepared to have him call the shots for the next dozen years or so, you must establish without delay that you have the final word, and that he has no choice but to listen. Be fair though, and be sure it's defiance and not confusion. Punishing a dog when he doesn't know what his offense was is destructive. When your pup has backed away several times upon command, or even better, accepted the fact that the boot is forbidden and has ignored it for two or three days, you can safely say that he has mastered the idea.

“And now if your ‘No’ is without effect, or if he decides to return the boot, he is doing nothing less than challenging your authority. It's time to let him have his first Mean Talk”

–and that's mean talk with a capital M capital T —

“Take him firmly by the scruff of the neck. Bring your face about a foot and a half from his and cut loose with a blast of raw anger. ‘You are the most rotten, despicable creature I've ever seen! You're going to have to shape up, understand? You miserable, no-good excuse for a dog. You try that one more time and I'm going to fly you from the flagpole and bounce you all the way downtown and back.’

“Give him about 20 seconds of this. Believe me, he'll be impressed. With most pups, you'll only have to do this once or twice. If yours is especially resistant, you can finish up with a quick finger snap or slap to the muzzle, but this is usually unnecessary. Some very clever pups will ignore a warning until you move to correct them. Then they respond with lightning speed and look at you with feigned innocence thinking, ‘Haha, beat you to it. Can't give your good and obedient puppy dog a hard time now.’

“But you most certainly can. And you must. If you don't, this dog will play the same game, ‘Catch the master stupid,’ throughout all his training and his later performance, failing to respond until you make some overt move toward him. Correct him just as if he had ignored you altogether. He'll know what it's all about. You teach them in this way; that correction is inevitable, that he is not going to get away with it, no matter how subtly he attempts to disobey.

“If he scoots away, don't stand there demanding he return and don't bellow and chase him around the house. How would you like to be pursued by a storming 50 foot creature? That's the approximate size ratio. Strive purposefully and silently after him, catch hold of the ever handy sash cord, haul him back to the scene of the crime, kneel down, take him by the scruff, and deliver your sermon on the many liabilities and drawbacks of being a disobedient dog.

“Follow this procedure for all phases of pup disciplining. Remember that the finger snap, the muzzle slap, and the newspaper are to be used only as last resorts. Also limit the finger snap and the slap to offenses involving the mouth, e.g, chewing, barking, nipping, where there's a direct relationship. The newspaper is appropriate for other transgressions.”

So, this is a lot like much of the training I grew up doing with my dog and a lot of what we were told. You have to be consistent. The muzzle whack was something that I remember learning, the deep voice, the guilt trip. I've talked about that before. And that's kind of what he's doing. It's just like the grandpa guilt trip.

Which makes me think about what it's like to hear people talk to their dog in a foreign language. If you've ever had that experience, watching someone talk to their dog in a language you don't understand. Which actually also kind of makes me think of when you see like a celebrity magazine in a foreign place that has people on the cover that you don't know and names you don't know, rather than like the celebs that you are familiar with from home. You get the general idea, but it's sort of meaningless.

Anyway, what I think is interesting here is how much he assumes the dog is understanding, down to the specific words that you use in your takedown. Anyway, pretty harsh stuff here, and certainly some things I'd call a bit of malarkey. But he certainly speaks some truths where, you know, it's unfair to punish a dog if he doesn't know what he's being punished with. He makes that point, although he doesn't quite describe how he ends up making sure the dog understands what he's being punished for. Although I guess eventually the dog stops doing the behavior, which makes it clear he has understood it in some way. Because if a behavior has been effectively punished, it should stop happening after not too many times.

But, anyway, lots of interesting dog mind-reading happening here, which I thought about a few pages later when I got to the part where he's talking about teaching a Stay. He says:

“Put your dog in a sit, then, place your hand a couple of inches in front of his eyes and say, ‘Stay, Samson, stay.’ For some reason no one has fully understood, a brief blocking of vision conveys the message instantly to many dogs. And it is helpful even to those who don't fully comprehend it.”

So I read this and I thought, but hold on, you were just telling me all these things, you know about what a dog knows, and you don't know why this works? Also, this is the kind of like dog training snake oil stuff that people love and is so frustrating. Like it doesn't make any sense. Okay. Maybe, again, maybe I'm wrong. Maybe I'm being a cynic. Maybe there are really peer reviewed journals that have published studies where they worked with two different groups of dogs to train Stay. And one was a control group, and one was a group where they held the hands over the dog's eyes briefly, which I think is what he's suggesting.

There's a photo of him doing a Stay, but he's holding out his hand in front of him while the dog is sitting and he's holding a taut leash. But the hand isn't really in front of the dog's eyes. Maybe he means like blocking the vision between you and the dog, the sight line? Anyway, it's unclear. But this is the kind of dictum that people love to follow when an expert says it, even if it makes no sense.

Like I've said on the podcast before, sometimes I feel like I could go into someone's home and say like, “The way to get your dog to stop peeing inside is going to be jumping up and down three times on one foot and yelling the word raspberry before you take them out.” And like, I feel like sometimes people would do it because they want to grab onto something. It's like the whole Cesar Millan, you know, never let your dog go through the doorway before you. He said it. We trust he’s right, even though we shouldn't. Anyway.

So he says: “For some reason, no one has fully understood a brief blocking of vision conveys the message instantly to many dogs, and it is helpful even to those who don't fully comprehend it. Immediately after ordering your dog to stay, back three feet away from him. He'll most likely try to follow you. Step forward and place him back in position. Tell him ‘No, sit, stay. Sit, stay. Stay!’ Back away again, repeating ‘Stay, stay. That's it. Good boy. Stay.’ Then be silent, and speak only when it looks as if he's about to break, say, ‘No, stay, stay!’ Put him back into position each time he moves.”

So this is certainly how a lot of people teach Stay. And I'm not sure if it's in a book because this is the way a lot of people teach Stay, or if people teach day because Rudd Weatherwax taught Stay this way. Again, worth noting the reliance on language here, as if the word is causing the dog to do it, or as if the dog specifically understands that word when you've just introduced it. I think it's actually probably a kind of negative reinforcement that's encouraging the behavior of sitting in these sorts of situations. Because the dog is like, “You know what? I'm just going to keep my butt on the ground. Cause that keeps him from yelling that annoying word at me over and over.”

There's a lot of overlap in the dog training advice he gives and the dog training advice that was spewed by Barbara Woodhouse, who was a huge celebrity trainer in the early 1980s, late seventies, I think in England, particularly. She was on the BBC. In the problem solving section of the book. He suggests something similar to what I know she suggests for dogs that chase cars or bicycles. He writes, “Have a passenger ride along with the driver, carrying either a child’s water pistol or a bucket full of water. When the dog comes running up abreast of the car, the passenger shouts, ‘No! No bad dog. No, no,’ and squirts away at the dog's face with a pistol or dumps the entire contents of the bucket over him in one swoop.”

If a dog jumps, he wants you to knee the dog in the chest. If a dog is digging, he says you should throw a bunch of tin cans at them. And here he is on dogs sleeping on furniture:

“Curing your dog of sleeping on furniture while you are at home is simple. Catch him in the act, rush to him with indignation, and give him a stern lecture. ‘What are you doing? Bad dog. Get off there. Bad dog. Get off.’ Some dogs are devious. Though sound asleep on the couch, one ear is always cocked, and when they hear you approaching, they're often a single bound and lying innocently on the floor by the time you enter the room. You must be sneaky with these. Take off your shoes, creep silently down the hall and burst in upon them before they know you're coming.

“A few will be too perceptive and quick to matter how skillful your attempts. You can tell if he's trespassing. The cushions will be warmed from his body heat. There may be hairs present. If that's the case, take him by the collar, haul him over to the piece of furniture and dress him down.”

And actually, Annie speaking, now, this is funny because my dad used to make a really big deal about not wanting our dog on his bed, which I think he thought of as some kind of power thing, because it wasn't, I don't think about cleanliness. My dad was far from being a neat freak. And he liked snuggling with her and stuff. But anyway, I remember even as a kid though, kind of realizing that she had figured out that it was okay to be on the bed as long as he wasn't home.

And you know, there would be these like Mabel shaped impressions on his bed, and he seemed kind of okay with that. But then years after Mabel, we had a cat that we inherited and felt obliged to take care of, but he was a really mean cat and nobody liked him. And my dad really didn't want the cat on his bed. And for the cat he did what Rudd Weatherwax says to do, actually. Rudd Weatherwax writes:

“The dog who settles in for leisurely snooze on the furniture as soon as you've left the house is another problem. To be effective, remember, correction must come immediately on the hills of the offense. Buy some mouse traps from your local hardware store, set them, then place them eight or nine inches apart on whatever pieces of furniture your dog favors just before you leave the house. Cover them with one or two sheets of newspaper.

“When the dog leaps up, he's going to encounter one rousing, big surprise as the mousetraps go clicking off, rattling and snapping the paper under his feet and haunches, and he'll rocket back to the floor. Don't worry about him being hurt. He won't be. The small traps are very strong and the layer of paper prevents the bars from coming down on his toes or pinching his hair. If you own one, though, and are still a little unsure, you can settle your mind by having the clerk at the hardware store, weaken the springs for you.”

That's all for this week. Special thanks to the YouTube channel, The Great Whistler for his wonderful whistled version of the Lassie theme song.

[Whistled Lassie Theme plays]

I have a new free ebook which I'd love to share with you. It's on three dog training techniques you can use on people. You can find it schoolforthedogs.com/people. If you are going to use a mouse trap to teach your dog to not get on the bed, do make sure to loosen the springs, but also you might want to find a different podcast to listen to. The rest of you, I'll see you next week.

Links: